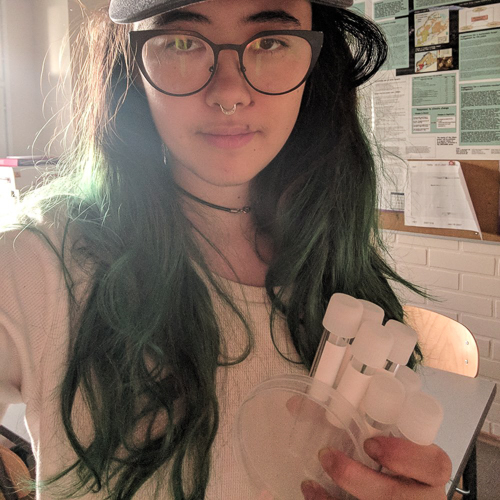

Rabía Williams (ACA)

Through the telephone headset you can hear the AM long-wave radio, recognizable as radio with help of the diode.

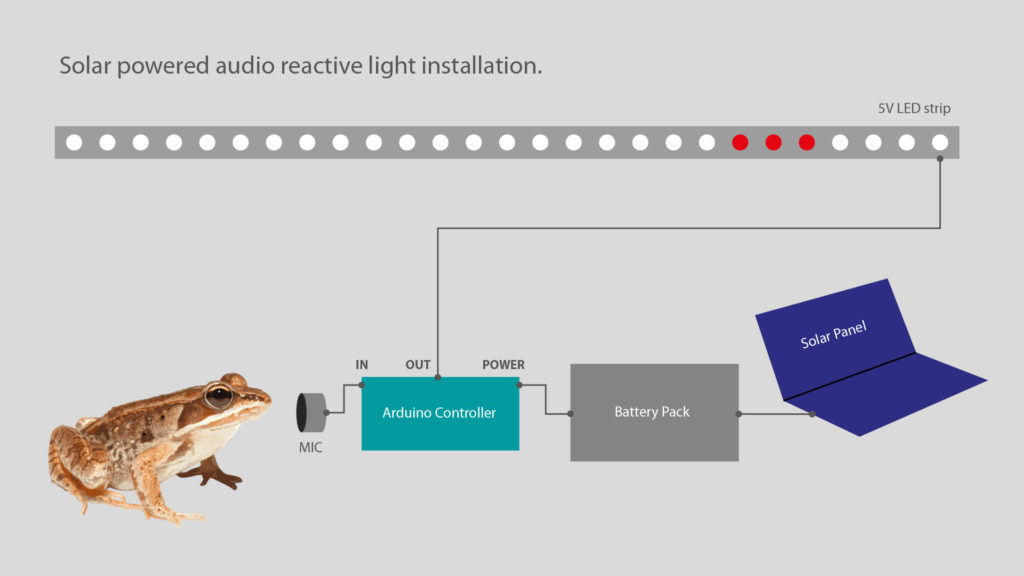

AM receiver consists of:

- Two coils (copper wire 22): 1st band of 40 turns and 2nd band 30 turns

- 1N34A Germanium diode

- 47k Capacitor

- Variable Capacitor

- Telephone headset – headphones

- Insulated wire: 50ft for antenna / 25ft for grounding cable

Pulling radio waves, tapping in, circuiting, a translation, somehow nothing feels so present as working with radio waves. But it is rather an act of presence. Distance is compressed. There is a leap in time. Wrapping the coil around the object keeps one present. If you are counting the turns, as any good crystal radio aficionado is supposed to, you cannot lose yourself in the action fully. I sometimes did this canal-side. It feels like a mantra.

During my time at Dinacon I was making radiophonic objects to create kinds of living documentary installations working with radio waves, found and archive objects and sound – the

so-called inanimate, the man-made and the natural. They are something like witness objects.

I brought the pill bottle at the center of this pod from my grandmother’s house. Both my grandmother´s parents lived for a time in Panama, individually emigrating from the West Indies to Panama before coming to the States and eventually meeting each other in a church in Bedford–Stuyvesant, over 100 years ago. This pill bottle is for thyroid medication. My Grandmother´s thyroid was damaged as a child, burned through iodide painting, an experimental practice of the time. This left her with a permanent thyroid condition that she has been taking medicine for ever since.

I spend time in Gamboa´s Soberanía rainforest, sometimes recording alone and others times with Dina colleagues who made exploring a much more curious experience…

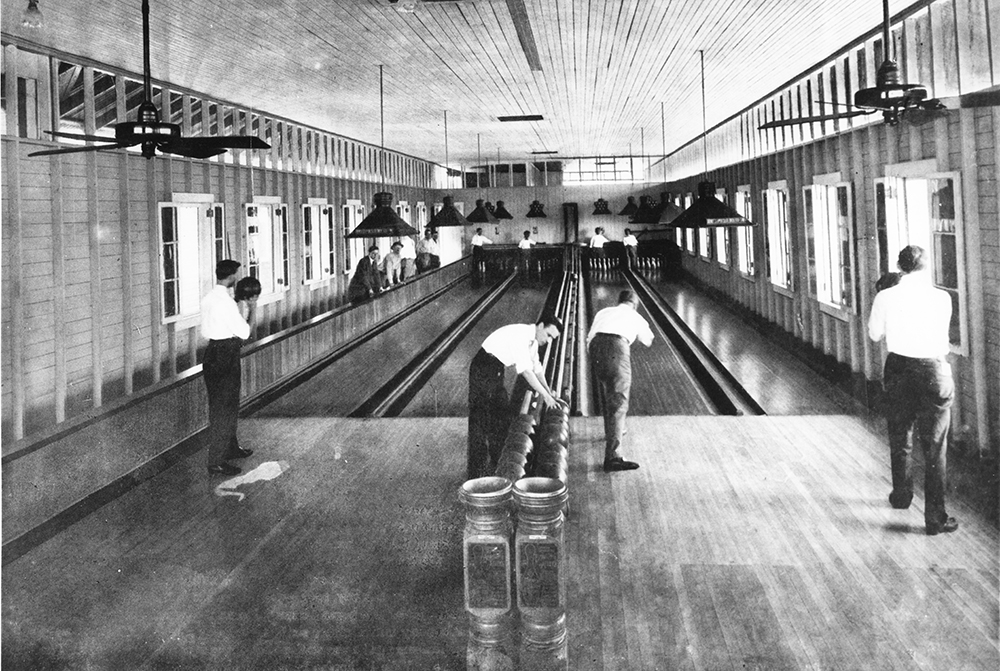

Mostly the village of Gamboa seems like a ghost town, abandoned structures and houses. You could easily walk the loop of the town without crossing another pedestrian.

But it does not sound like you are alone! Two sonar worlds seemed to rule here, the balance unknown:

1) That of the jungle, which the town is carved and shaved into. These are sounds from inside the trees, the dirt, and grass, and the sky above. As I rendered these sounds into words I think of my childhood books, a collection of descriptions: roaring, picking, tweeting, buzzing…, amongst my first words practiced just after Moma and Dada and no, no, Rabía no!

2) The other sonar world sounds from the bordering canal. “Canal” is quite appropriate: a vibrating, tremble, something like a “horn blows low”. It is a recognizable machine-at-work sound. And water.

Does the nature remember, what?

The people remember the territory occupied. They remember who lived on which side of town. Pastor Wilbur explains: “The Black West Indians lived on this side…”

This town exists as an important drenching point. Here in the town of Gamboa the land is always sliding into the canal and must constantly be dredged.

I often wander around Gamboa town and I sometimes go to Panama city for supplies. I record folks I meet, not on the street but along the way: a young man who is the son of Panamanian canal engineer- one of the only in his position during those times when Americans ran everything to do with the Canal; an American pastor recruited to preach in English over 40 years ago; and the local sign builder. And I collect sound archives.

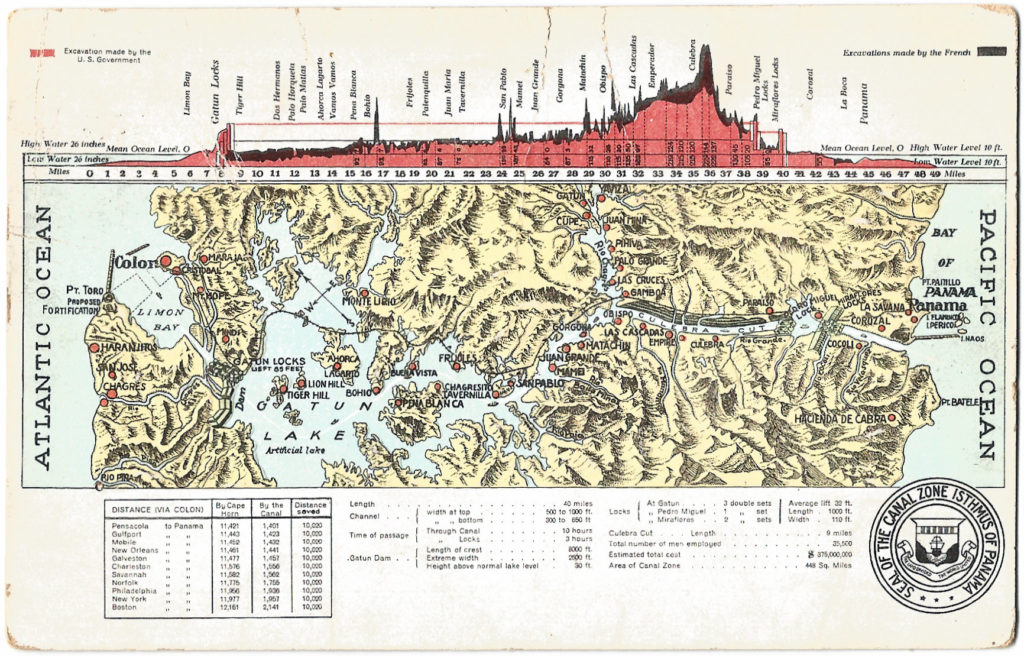

The Americans came up with the locks as a solution for the canal project the French gave up on.

Matthew Parker:

“[The canal] did not so much impact on the environment as change it forever. Mountains were moved, the land bridge between the north and south American continents was severed, and more than 150 sq miles of jungle was submerged under a new man-made lake. To defeat deadly mosquitoes, hundreds of square miles of what we would now call “vital wetlands” were drained and filled, and vast areas poisoned or smothered in thousands of gallons of crude oil.”

– Changing Course, The Guardian

Many lives have been lost in the building of the canal, most to accidents and others to yellow fever. The majority of lives lost were black men from the West Indies. Thousands died drenching the canal – over 20,000.

I recover items from the River Charge: flip-flops, obviously modern, so many types and sizes of flip-flops -there is something about shoes that are haunting – and find lots of pesticide containers and bottles of many different sorts.

Experiencing radio silence for a couple of days there! Testing ground connection with Philip. It seems so simple what the F is going on.

Finally, thanks to Philip we realize what the problem was – the simplest always gets ya.

Here striping cable to remove the installation preventing any radio waves from entering the cable.